Oosoji (大掃除), Japanese Big Year-End-Cleaning

By Yukari Yamano

In December, the Japanese conduct a year-end-cleaning. They clean houses, schools, offices and public spaces to prepare for the coming New Year. It is called Oosouji (大掃除), which literally means “Big Cleaning.”

The tradition goes all the way back to Heian period (794 – 1185). It started out as a court event called “Susuharai (煤払い), an annual cleaning away of soot and dust. The Heian law book, Engishiki (延喜式, completed in 927) explains in detail how to conduct Susuharai. Back then, a main reason for the cleaning was to drive evil spirits away from the court and welcome Toshigami sama (年神様), the Shinto New Year’s deity. In the Muromachi period (1336 – 1573), shrines and temples became the center of Susuharai ritual cleaning.

Left: Kashima Jingu Shrine Susuharai (the picture is from Mainichi.) Right: Daiyuzansaizyoji Temple Susuharai (the picture is from Kanagawa Town News)

During the Edo period (1603 – 1868), common people adopted the custom and conducted a big cleaning as a very first activity of New Year’s preparation. They thoroughly cleaned their homes before decorating with auspicious objects such as Kadomatsu (門松, New Year’s pine and bamboo decorations) and Shimenawa (しめ縄, sacred straw festoons) to welcome Toshigami sama. A big cleaning has been a very important event for all Japanese since then.

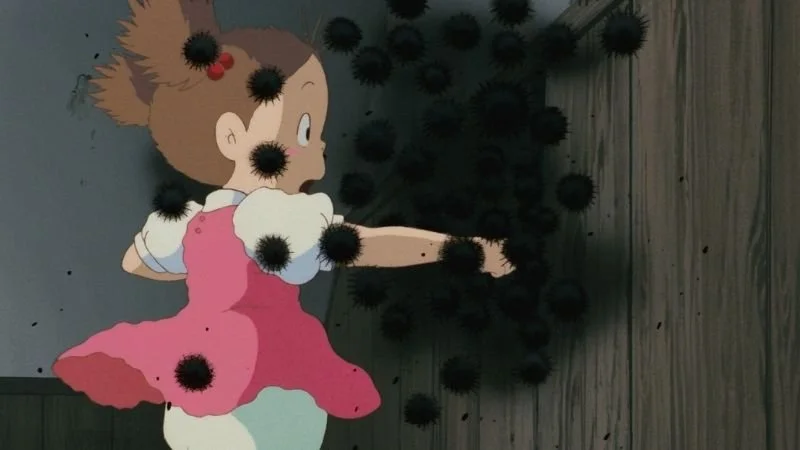

Susu means “soot” or “smoke dust” in Japanese, and “harai” means “sweeping.” Before electricity, people used candles for light and hearths for heat and cooking. Houses accumulated soot throughout the year and really needed to be cleaned periodically. In the animated movie, My Neighbor Totoro, there is a scene in which one of the main characters, Mei, tries to grab a round black sooty sprite. She calls it Makurokurosuke, or “Pitch black.” Later, an elderly neighbor explains to Mei and Satsuki that they saw Susuwatari, soot travelers (ghosts)!

The animated movie, My Neighbor Totoro one scene that Mei encounters Makurokurosuke (the picture is from Studio Ghibli)

December 13th became the traditional day of Susuharai (煤払いの日) in Edo (now Tokyo.) It was a big event for the people of the town!

Cleaning took place in castles, lordly residences, temples, shrines, stores and houses. Merchants sold Susutake (煤竹), or soot-cleaning-bamboos, and could be heard peddling their wares throughout Edo. At many merchant stores, after cleaning was completed, both owners and workers tossed each other into the air to celebrate. The owners served mochi to their workers, and after that, everyone went to bathe to clean off the soot and dust. This bath was called Susuyu (煤湯), or “soot-bath.” After bathing, the owners served sake to their workers and let them go home early.

Ukiyoe: Genji Jūnikagetsu no Uchi Shiwasu by Kunisada Utagawa (歌川 国貞) Copyright: Waseda University Library

Many Haiku poets wrote songs about Susuharai, including the famed Matsuo Basho and Kobayashi Issa.

Basho sang:

旅寝して見しやうき世の煤払ひ (Tabineshite Mishiya Ukiyono Susuharai)

At my traveling bed

Overlooks the World’s

Susuharai

Here, the poet is saying that the public is busy with soot and dust cleaning while he’s just a bystander, since he spends all his time traveling.

Issa sang:

我が家は団扇(うちは)で煤を払ひけり (Wagayawa Uchiwade Susuwo Haraikeri)

At my house

A paper fan is used for

Susuharai

Here, the poet is saying that at his house, they clean soot and dust with a paper fan, meaning the house is too small to use bamboo duster.

Perhaps, this December, Seattleites can clean their homes to welcome Toshigami sama, too. We wish you a happy holiday!

You can also read about Japanese New Year's Decorations.

Yukari Yamano is an event coordinator at the Seattle Japanese Garden, a native Japanese.